When Disneyland Paris (or EuroDisney as it was then called) opened in 1992, the French were thoroughly sniffy about finding themselves hosting a theme park engineered by an iconic symbol of American culture and enterprise. Allowing Mickey to set up home in Marne-la-Vallée was, it seems, the worst thing to have happened since Hitler visited Paris in 1940. However, the French were, it has to be said, no more sniffy than we would have been if EuroDisney had been built on British soil where the cries of ‘American Imperialism’ would have been equally deafening.

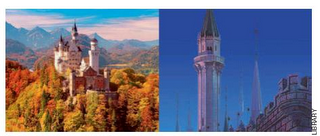

When Disneyland Paris (or EuroDisney as it was then called) opened in 1992, the French were thoroughly sniffy about finding themselves hosting a theme park engineered by an iconic symbol of American culture and enterprise. Allowing Mickey to set up home in Marne-la-Vallée was, it seems, the worst thing to have happened since Hitler visited Paris in 1940. However, the French were, it has to be said, no more sniffy than we would have been if EuroDisney had been built on British soil where the cries of ‘American Imperialism’ would have been equally deafening.At the Grand Palais in Paris where the exhibition, Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l'art des studios Disney is in its final days, the only reference to the fact that Disney has a colonial outpost 45-minutes by Metro from the heart of Paris is a superb scale model for Le Château de la Belle au Bois Dormant in a section showing the influence of European architecture on the designs made by Eyvind Earl for Disney’s 1959 film, Sleeping Beauty and, thence, to the physical castle in the French park.

The fact that Disney can be the subject of this major ‘art exhibition’ without once again raising the French hackles is interesting, but then it is Disney observed from a very European perspective in that it seeks to show the extent to which the literature, art and films of Europe influenced Disney and his artists and inspired the styling and design of three decades of animated feature films - from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book - that are usually thought of as being quintessentially American creations..

The exhibition takes its inspiration from the book Walt Disney and Europe: European Influences on the Animated Feature Films of Walt Disney by my dear friend Robin Allan and to which I was privileged to contribute a preface. Robin's book was, and remains, a groundbreaking work of cinema scholarship which reveales how Disney personally admired and collected the published work of such illustrators as Doré, Daumier, Arthur Rackham and Beatrix Potter as well as employing a number of European artists to work on his films including Kay Nielsen (from Denmark) and Gustav Tenggren (from Sweden) and who were both prolific fantasy book illustrators and brought their graphic brilliance to bear on such Disney films as Fantasia and Pinocchio.

The exhibition takes its inspiration from the book Walt Disney and Europe: European Influences on the Animated Feature Films of Walt Disney by my dear friend Robin Allan and to which I was privileged to contribute a preface. Robin's book was, and remains, a groundbreaking work of cinema scholarship which reveales how Disney personally admired and collected the published work of such illustrators as Doré, Daumier, Arthur Rackham and Beatrix Potter as well as employing a number of European artists to work on his films including Kay Nielsen (from Denmark) and Gustav Tenggren (from Sweden) and who were both prolific fantasy book illustrators and brought their graphic brilliance to bear on such Disney films as Fantasia and Pinocchio.

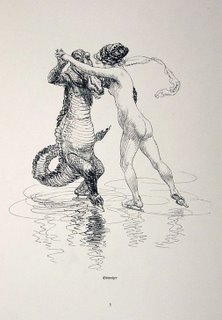

Like Robin Allan's book, the exhibition brings together Disney images with likely sources of inspiration including, among many others, the temperamental Tinkerbell from Peter Pan with the Rackham’s fairies in Kensington Gardens, the tea-cup hopping mice in Cinderella with those in Beatrix Potter’s The Tailor of Gloucester and the anthropomorphic hippos, elephants and alligators in Fantasia with those penned by Heinrich Kley, of whose fabulously bizarre drawings Disney had a huge private collection.

The exhibition represents Disney - nowadays habitually the subject of criticism and vilification - as a supreme visual storyteller whose films are a true continuation of the oral tradition that gave the world a catalogue of beloved fairytales and fables that in turn birthed the geniuses of Hans Christian Andersen, Lewis Carroll, J M Barrie, Rudyard Kipling, Felix Salten, P L Travers, Dodie Smith, T H White and the other authors whose books for good or ill (depending on your point of view) received the ‘Disney treatment.’

Once Upon a Time, Walt Disney provided a rare opportunity to examine, up close, some of the exquisitely detailed sketches and vibrantly energetic paintings that established the style and tone for the studio’s films, set alongside a raft of artworks from engravings by William Blake to paintings by Richard Dadd and extracts from such films as F W Murnau’s Nosferatu and Faust, Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr Caligari and James Whale’s Frankenstein. It is a series of intriguing journeys from idea and image through to the combination of cell paintings and watercolour backgrounds each of which represent a 24th of a second of animated film magic.

2 comments:

I'm glad you emphasise the European side of Disney's story. It always annoys and amuses me when little kids with whom I work are astounded when I tell them that I READ Winnie the Pooh or such other stories when I was little... "Gosh! Did it already exist then?"!! So few people realise that all these stories were European books eons before Disney ever got his (clever) hands on them!

What many people overlook is that Disney almost always visually decalred the literary origins of his films: 'Snow White', 'Pinocchio', 'Cinderella', 'Sleeping Beauty' - yes, and 'Winnie-the-Pooh' - all open with an opening book.

In the case of 'Pooh', the Disney artists used the turning page motif throughout the films - having the rain that floods Piglet's house wash the letters from the page or the winds of the blustery day blow them away...

Post a Comment