My secondary school - being a Sec. Mod. - only taught French to the kids in ‘A’ streamed classes and since I was never an ‘A’-stream pupil I never learned to Parlez Français!

My secondary school - being a Sec. Mod. - only taught French to the kids in ‘A’ streamed classes and since I was never an ‘A’-stream pupil I never learned to Parlez Français!This was a disappointment in only one regard: the school library contained all the ‘Tintin’ books in French - a smart move by an enlightened headmaster who saw it as a way of encouraging those ‘A’-streamers to revise while reading the amazingly exciting exploits of the best boy-adventurer ever!

As a lover of comic art, I used to pore over those books, trying to follow the stories without being able to read the ‘speech bubbles’.

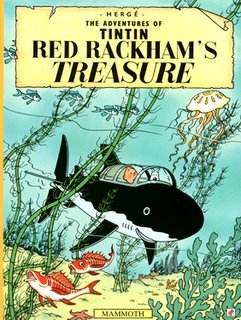

It was some time before I discovered that Belgian author and artist Hergé’s books were also available in ENGLISH! After that, I was able to enjoy The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Shooting Star, King Ottakar’s Sceptre, The Secret of the Unicorn, Red Rackham’s Treasure, Destination Moon, and the rest of Herge’s 23 books featuring Tintin the intrepid boy reporter and his dog Snowy, or Milou in French.

It was some time before I discovered that Belgian author and artist Hergé’s books were also available in ENGLISH! After that, I was able to enjoy The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Shooting Star, King Ottakar’s Sceptre, The Secret of the Unicorn, Red Rackham’s Treasure, Destination Moon, and the rest of Herge’s 23 books featuring Tintin the intrepid boy reporter and his dog Snowy, or Milou in French.The series also introduced what is now several generations of fans to a fascinating pantheon of evil villains and eccentric friends such as the Thompson Twins (the frightfully English duo of bowler-hatted detectives), Captain Haddock and Professeur Tryphon Tournesol - or to us, non-French speakers, Cuthbert Calculus.

Rounding off our recent lightning visit to Paris was a chance to see an excellent exhibition at the Centre Pompidou devoted to the work of Hergé.

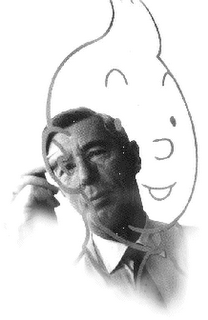

Born Georges Remi in 1907, he adopted the pseudonym Hergé from a reversal of his initials ‘R G’. The exhibition traces Tintin’s career from his first adventure Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, which began serialization in the pages of the children’s magazine, Le Petit Vingtième on January 10, 1929 through to Hergé’s preliminary drawings for his final, 24th, book left unfinished at the time of his death in 1983.

Born Georges Remi in 1907, he adopted the pseudonym Hergé from a reversal of his initials ‘R G’. The exhibition traces Tintin’s career from his first adventure Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, which began serialization in the pages of the children’s magazine, Le Petit Vingtième on January 10, 1929 through to Hergé’s preliminary drawings for his final, 24th, book left unfinished at the time of his death in 1983.As the exhibition shows, Hergé was not just a comic book artist (though he was a supreme craftsman of that medium with his ability to master the “trick” of “a clear, steady line”), but also a novelist - albeit a graphic novelist.

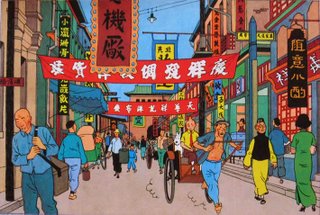

His painstaking attention to research and detail - a significant feature of his work from the seminal story The Blue Lotus, in the writing of which he had been encouraged by Chang Chong-jen a young Chinese sculpture student who became friends with Hergé while studying at the Brussels Académie des Beaux-Arts.

The portrait that emerges of Hergé is of a man who discovered his vocation very early in life - his first childhood pictures were drawn in comic book format - and who pursued his art with a passion to the extent that when making his drawings he would be so energised and intensely involved in his work that the pressure with which he applied the pencil would often cut right through the paper!

The portrait that emerges of Hergé is of a man who discovered his vocation very early in life - his first childhood pictures were drawn in comic book format - and who pursued his art with a passion to the extent that when making his drawings he would be so energised and intensely involved in his work that the pressure with which he applied the pencil would often cut right through the paper!My favourite anecdote gleaned from the exhibition is this recollection by Hergé of his early artistic endeavours: “One day, a pupil took my drawings and showed them to the head teacher Mr Deschamps. He looked at it with a disdainful frown and told me: ‘You will have to produce something different to be noticed.’”

And much - perhaps everything - that one needs to understand about Hergé’s success is found in a statement that he once wrote about his creations: “I love my characters, I believe in them. To me, they are real people. I think I would react they way they do if I found myself in the identical situation in which I place them.”

2 comments:

How lovely to see our Belgian hero in your blog!

A couple of things you may not know about Hergé's writing.

The names of certain caracters, places and even parts of the dialogues were inspired from a dialect spoken in the centre of Brussels "Brusseleer".

The "Château de Moulinsart" where Capitaine Haddock lived was also inspired by a real place in Belgium.

Thank you, Suzanne... And, yes, Mr Scrooge, you are right, and as the exhibition makes clear, it was Herge's friendship with his Chinese friend Chang that had the most powerful impact on how those stories were were written...

Here's what Wikipedia says on the subject:

"Hergé reached a watershed with 'The Blue Lotus', the fifth Tintin adventure. At the close of the previous Tintin strip, 'Cigars of the Pharaoh', he had mentioned that Tintin's next adventure would bring him to China. Father Gosset, the chaplain to the Chinese students at the University of Leuven, wrote to Hergé urging him to be sensitive about what he wrote about China. Hergé agreed, and in the spring of 1934 Gosset introduced him to Chang Chong-jen (Chang Chongren), a young sculpture student at the Brussels Académie des Beaux-Arts. The two young artists quickly became close friends, and Chang introduced Hergé to Chinese history, culture, and the techniques of Chinese art. As a result of this experience, Hergé would strive in 'The Blue Lotus', and in subsequent Tintin adventures, to be meticulously accurate in depicting the places which Tintin visited. As a token of appreciation, he added a fictional 'Chang Chong-Chen' to 'The Blue Lotus', a young Chinese boy who meets and befriends Tintin. In the book, the fictional Chang serves to dispel some of the more outrageous fabrications about Chinese culture."

One of my favourite images in the exhibition - which (sadly) I couldn't find for reproduction - shows the Dalai Lama reading 'Tintin in Tibet' with a huge smile on his face!

Post a Comment