There was a time when I used to think of

Tove Jansson, the Finnish artist and writer who wrote in Swedish, as being someone in whom I had some kind of private and personal ownership!

Photograph: Lehtikuva Oy

Devotees of Tove Jansson's Moomin characters were, it seemed, a relatively select group; while those who knew anything about the writer and artist, her life and her other work were far and few between.

Not so today!

Whereas, just a few years ago, when writing a blog post about Tove, I felt the need to begin with some sort of explanation:

What is a Moomin?

Well, you could say it is something like a small white hippo but with a

bit more tail –– but that really doesn’t get you very far… Basically, the thing is – when it comes to Moomins – you’re either a Moomin person or you’re not… If you're not then you've probably already stopped

reading, but if you're still there, then I ought to introduce you to the

Finn Family

Moomintroll: Moominpapa, Moominmama and their son Moomintroll.

And, of course, all Moomintroll's highly individual friends: Snufkin and Sniff, the Snork and the

Snork Maiden, the Muskrat, Tooticky, Ninny, Mimble and Little My,

assorted Hemulens and Thingumy and Bob. Not to mention the terrifying Groke and the spooky Hattifatteners...

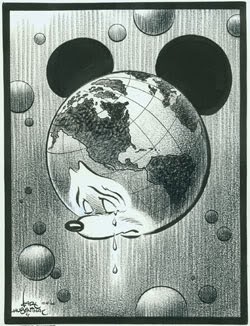

Today, however, the Moomins are a worldwide franchise – pictured on a veritable department-store of merchandising – and their creator is now recognised not just as the writer of a series of extraordinary children's books, but also as a novelist and short story writer of unique style and as a exceptional painter.

Some of the many talents of this amazingly gifted woman are currently being celebrated with an exhibition at

Dulwich Art Gallery:

Tove Jansson (1914-2001) that remains

on show until 28 January 2018.

Moomintroll is waiting by the entrance to welcome you in...

The exhibition opens with examples of Tove's early imaginative paintings that are stylistic explorations, obliquely foreshadowing the creation of Moominland...

Tove came from an artistically-gifted family that were part of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland. A stunning group portrait in the exhibition shows Tove in the centre, in black – looking curiously ill at ease – with, right, her father, the sculptor, Viktor Jansson, and, left, her mother,

Signe Hammarsten-Jansson, an illustrator and graphic designer whose work included the designs for some 220 Finnish postage stamps across three decades. In the foreground, at the chessboard, are her brothers, Lars (who would later take over the Moomin comic strip from Tove) and Per Olov Jansson who would become a successful photographer.

Tove's mother had worked for the Finnish satirical magazine,

Garm, and Tove began drawing for the publication in 1929 when she was only fifteen.

Tove contributed some 500 illustrations and caricatures to

Garm through the years of WWII and up until the magazine's demise in 1953. Among her contributions were dozens of cover blistering designs lampooning communism and Nazism.

The Moomins would take over much of her life – first as the books and then as a cartoon strip for a British newspaper and the exhibition celebrates this part of Tove's work with preliminary sketches and a number of intriguing variations on her published illustrations.

One of the surprising realisations from seeing her original art is the small scale at which she worked and the potency and dramatic intensity achieved.

Apart from Tove's memorable illustrations to the Moomin stories – some dense with detailing and cross-hatching, others almost impressionistic in their airy lightness of line – the exhibition includes examples of her evocative and idiosyncratic illustrations for three books by other authors: Lewis Carroll's

Alice in Wonderland and

The Hunting of the Snark and J R R Tolkien's

The Hobbit.

Her drawing of the Dwarves crossing the bridge to Rivendell (with the Elven boats on the river below) is a miniature masterpiece...

Following the phenomenal success of the Moomin books, Tove would return to painting for herself, trading-in the 'Tove' signature by which her work had been known for so many years for 'Jansson'.

These paintings include dramatic abstract seascapes that capture the northern wildness of her homeland and recall the storm-tossed exploits of some of her Moomin characters...

Also from this period is, perhaps, her greatest painting: a startling, uncompromising self-portrait that roots the viewer to the spot and haunts the memory...

Dulwich Picture Gallery are to be applauded for the imaginative way in which the exhibits have been displayed in a series of vibrantly coloured rooms that eventually lead the visitor into a space that makes you feel as if you have stepped into one of Tove's Moomin illustrations.

Wandering round this wonderful exhibition, brought back many personal Moomin memories...........

I first encountered the Moomins in 1954 in the daily comic strips, written and drawn by Tove, which appeared in the

Evening News that my Dad used to bring home from work each night.

Tove’s brother, Lars took over the strips in 1961, in which year,

Puffin Books (God bless ‘em!) published the first paperback edition of

Tove’s novel,

Finn Family Moomintroll translated from the original Swedish.

This was followed by, among others,

Comet in Moominland,

Moominsummer Madness,

Moominland Midwinter and

Tales from Moominvalley. Eight novels in all, plus various delicious picture books…

What captivated me about the chronicles of Moominland

was the combination of fantastical storytelling with exquisite

black-and-white illustrations that evoked feelings of warmth, happiness

and security, shadowed by a hint of sadness, longing and regret, and

tinged with a kind of yearning that is both nostalgic and elegiac.

In Moominvalley, everyone – however curious, odd or downright difficult: an

invisible child or a cross-dressing Hemulen – is welcomed and

accommodated somewhere in the tall, tower-like, Moomin House.

It is a tolerant world in which love is unconditionally guaranteed and where every individual is allowed – actually

encouraged – to be themselves without criticism or censure; a world where home is

the safe, centered heartbeat of life to which the inhabitants always

return but from which they are also free to set off on adventurous

quests in search of whatever might lie over this mountain or beyond that

sea…

I always wanted to write to Tove as a youngster, but to a child

of the ‘50s, Finland might as well have been on the moon; and, indeed,

Tove (with her life partner, the artist Tuulikki Pietilä – not that I knew about her, at the time, unconventional private life), lived on a

small island called Klovharu, that, in the days before instant global

communications, was about as remote as you could wish an island to be.

Although

I never wrote that fan-letter, I loyally maintained my love of

Moominvalley into adolescence and beyond, by which time I had found her

beautiful adult novel about childhood and old age,

The Summer Book.

Over the past few years

The Summer Book has been republished along with a companion volume of stories,

The Winter Book,

and several of Tove's novels and short story collections and,

accompanied by endorsements from the likes of Esther Freud, Ali Smith

and

Philip Pullman, her writing has found a new generation of readers.

Anyway, twenty years after first falling in love with the Moomins, I finally decided to attempt to make contact with their creator.

In the meantime, I had also discovered that Tove had illustrated

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

and since, at the time, I was working on a book (that has never seen the light

of day and, now, will never do so) about interpretations of Lewis Carroll’s story in the popular

media there was an added incentive to try to contact this literary and artistic heroine of mine.

So it was that, in 1975, we began a correspondence that ran, on

and off, until 1995, during which time, we exchanged letters and cards

and Tove sent me several books and a hand-drawn greeting that is now one

of my most treasured treasures…

Tove wrote to me at length about Hans Andersen and Lewis Carroll and talked about how, as a child, she had initially disliked the

Alice books:

Reconstructing

afterwards is difficult, one is afraid not to be honest, but I believe

that I felt Carroll’s anguish and reacted by fright.

Of course, I read Alice

again, 20, maybe 30 years later, still without knowing anything about

Lewis Carroll’s life – and I was fascinated, enchanted. Most of all by

his unbelievable capacity of [sic] changing everyday reality into

another underground-reality, more real, overwhelmingly so – one dives

into the depths and stays there until the end. It is nightmarish...

As far back as I can remember, I have had nightmares, maybe that

was why I couldn’t like Lewis Carroll as a child. In 1966, when I

illustrated the Swedish translation of Alice in Wonderland, I read about his life, and understood…

Of Tenniel's original illustrations, she wrote to me:

"Tenniel was and is, to me the last word as to illustrating Alice, so I reflected a long time before taking on the job. It was like trying to paint Tahiti after Gauguin!"

Tove asked her Swedish publisher, Bonnier, to send me a copy of

Alice (this was in per-internet days when it was difficult to source foreign publications in the UK), but she later reported that they had no copies available, so she generously sent me one of her own – inscribed...

I was overwhelmed by both the gift and Tove's imaginative interpretation of Wonderland, I approached several British publishers on her behalf hoping that someone would take the book for the British market, sadly without success – rather as Tove had predicted:

"I don't think there will be any result. When I once sent them these illustrated books they liked my work but explained, very understandable, that they wanted to keep to their classics."

The artist also loaned me her last surviving copy of

Snarkjakten, the Swedish edition of

The Hunting of the Snark...

Later, Tove wrote to say I could keep the copy because she had found another. Though not inscribed, it has a very special association for me coming as it did from her own collection in the family's home on the island of Bredskär and carrying a beautiful bookplate designed by Tove's

mother, Signe "Ham" Hammarsten-Jansson...

A few years later, in 1978, Tove succeeded where I had failed and found an American publisher for her illustrations to

Wonderland.

On its publication, I received a personalised copy...

Being by this time a relatively successful broadcaster with a string of BBC

radio profiles of children’s writers to my credit, I made several

attempts to make a feature about Tove and her world.

We danced around the idea of my travelling to Finland to interview her, but she courteously eluded me for years and then, when she finally

turned 80 and was far from well, she wrote to say that she had at last

reached an age where she could now be excused a process which she had

“disliked and feared” as long as she could remember. “Now it’s final,”

she said, “and a great relief.” She signed off saying, “Hope you

understand. Have a fine winter…”

Of course I understood, but the disappointment was sharp and still smarts.

In our correspondence I had told her –

many times over,

I imagine – how much and why I loved her work, but, too late I realised

that there was still so many other things that I longed to ask her...

Had

I managed to find my way to her and Tuulikki Pietilä's little house on

Klovharu, I should have liked to ask her thoughts on Tolkien, especially since her illustrated

The Hobbit, like her drawings for

The Snark, had still not been published outside Sweden.

I would also have asked

about her extraordinary understanding of youth and age; about the sense

of longing and loss that runs through her books; and, most of all, about

her acutely-felt perceptions of love, parenthood and friendship. Then, if we had reached that far in the conversation, I

might even have had the courage to ask her perceptions on same-sex

relationships…

Well, alas, that was not to be, but in her letters to me she at least revealed some insights into the mysteries of creativity.

Here are just a couple of thoughts from the

Mistress of Moominland…

It is so very difficult to

know in what degree one’s work has been influenced… How can I know when

I portrait [sic] my own anguish, or dreams, or memories – or somebody

else’s? There [are] constant influences… a lot of them maybe part of the

big addition ending up in, say, writing or drawing…

Whatever they may be, they are possibly drowned in the

everlasting stream of impressions where one never knows what is one’s

own and what is a gift from outside…

One last snippet from those letters about that name – Tove –

that, as a youngster caught my eye and intrigued me... It was, she told

me, Norwegian:

"The first Tove, a princess, is said to have been buried in a sea shell. In Hebrew, 'Tove' means 'good'." Any Moomin fan will think both those linguistic

associations are appropriate to the person who put Moomin Valley on the map of our imagination...'

In the years since our correspondence and Tove's death, her illustrations to

The Hunting of the Snark have at last found their way into an English edition of the poem and some of her pictures for

The Hobbit have received limited exposure in Britain and the USA through their choice for the Official 2016 Tolkien Calendar for which I wrote an accompanying essay, 'From Moominland to Middle-earth'.

Then, this year, I received a request from the Finnish publisher WSOY for permission to include my essay as an afterword in a new edition of

The Hobbit with Tove's illustrations t

o

mark the 80th anniversary of the publication of Tolkien's story.

At the opening of the Dulwich Picture Gallery exhibition, I was thrilled to be able to give a copy of the book to Tove's niece (and keeper of the Moomin legacy), Sophia Jansson.

The exhibition, Tove Jansson (1914-2001) remains on show at the Dulwich Picture Gallery until 28 January 2018. There is a excellent, lavishly illustrated accompanying catalogue, price £25.00 on sale at the gallery or online.

Dulwich Picture Gallery

Gallery Road

London

SE21 7AD

Times: 10am - 5pm, Tuesday - Sunday (Closed Mondays except Bank Holidays)

© Moomin Characters™

Parts of this post first appeared on this blog in 2007.