All I did was put out an additional air-freshener because the one in use was running low and –– SHOCK-HORROR!! –– I unleashed this Miserable Loo Monster!

Wednesday 27 December 2023

Monday 25 December 2023

PEACE ON EARTH GOOWILL TO MEN

CHRISTMAS BELLS

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

"There is no peace on earth," I said;

"For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!"

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

"God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men."

Saturday 23 December 2023

WHY IS IT SUCH A WONDERFUL LIFE?

Being now almost now that eve of eves, means it is time to watch, yet again, my

favourite Christmas films – in fact one of my all-time favourite films whether it's Christmas or not! – Frank Capra's eternally satisfying and

edifying 1946 masterpiece, It's a Wonderful Life.

And if James Stewart – an actor too easily pigeon-holed as being a charming but lightweight player – ever gave a more nuanced performance than his portrayal of George Bailey, then I don't know of one, not even his barnstorming performance as the benign Jefferson Smith, Capra's All-American Everyman, in Mr Smith Goes to Washington.

From that turning-point onward, Stewart shifts his performance through a state of happy resignation with his lot in life to one of uncontrolled rage and nihilistic despair. That is when the heartwarming, some might say hokey, portrayal of small people nobly and courageously living out their small lives against all odds takes a darkly dramatic turn and the hero becomes a haggard, worn-down, tragic figure, ready to believe he would be better off dead.

Stewart's central role is surrounded, supported and enhanced by his fellow players: Donna Reed as the ever-loving, ever-caring wife, Mary, and Lionel Barrymore – famous for years for his annual radio portrayal of Ebenezer Scrooge – perfectly cast as that other "squeezing, grasping covetous old sinner", Henry Potter.

A Christmas Carol has inspired – or, if you prefer, spawned – hundreds of derivatives, but none has been more enduring or more deserving of celebration than It's A Wonderful Life.

Friday 22 December 2023

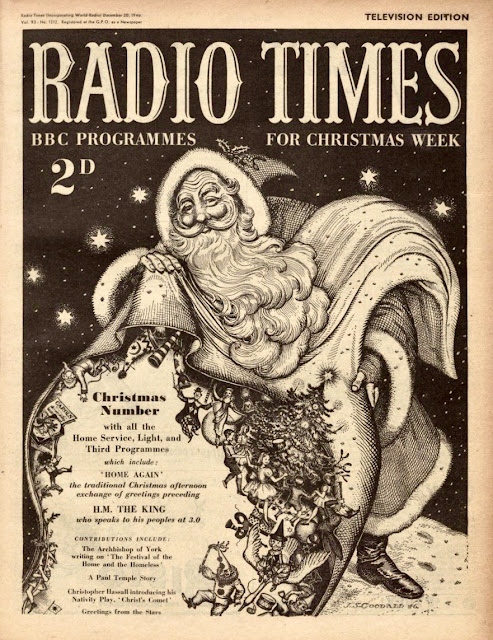

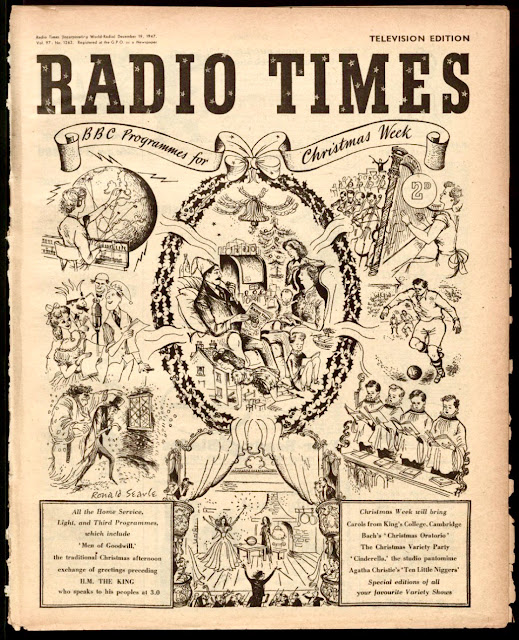

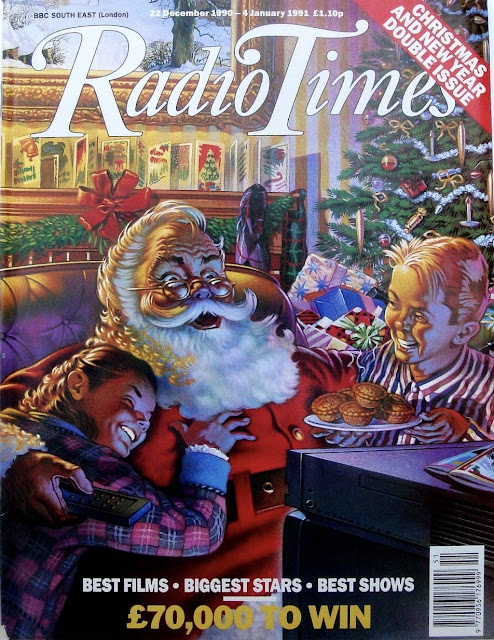

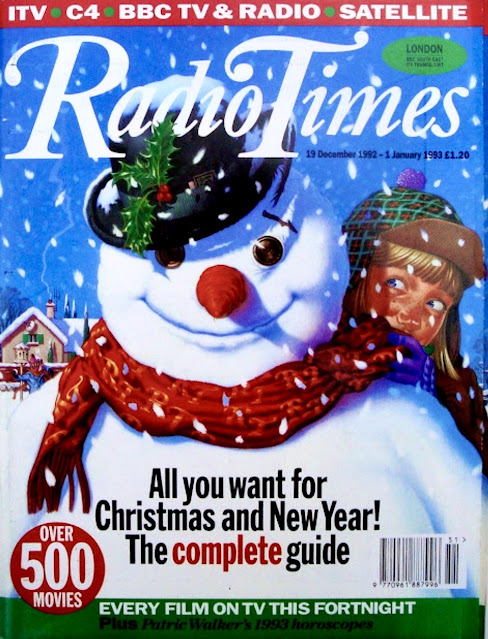

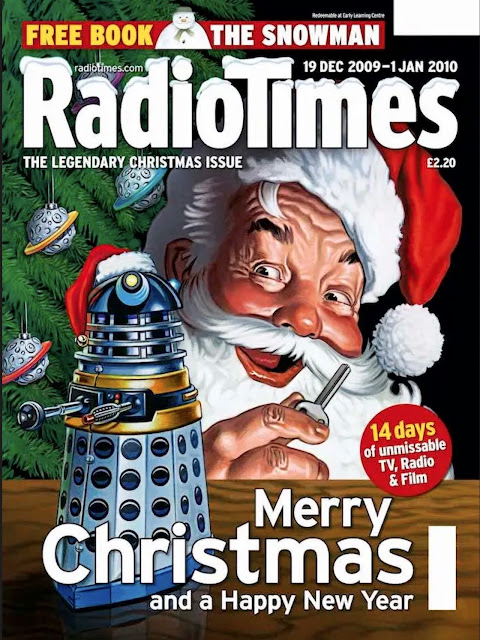

A 'RADIO TIMES' CHRISTMAS

Remember those days in the Twentieth Century when the arrival of the Christmas Issue (later 'Bumper Issue') of Radio Times signaled the true beginning of seasonal festivities?

Historically, Radio Times was always a showcase for the work of some of the finest graphic and illustrative artists of the age and examples of their work is showcased in this very personal selection of classic covers from before-my-time, but by artists whose work I love – John Gilroy (he of the classic Guinness posters), Rex Whistler, Edward Ardizzone and Eric Fraser; from my childhood and adolescent years – C. Walter Hodges, J. S. Goodall, Ronald Searle, Rowland Hilder, Victor Reinganum and, again of course, Eric Fraser; and, lastly, from more recent years – the impeccable art of Tony Meeuwissen and a wonderful cavalcade of Santas and Snowmen by my friend, Mick Brownfield.

Among the later are his Father Christmas and Dalek cover and the alternative variant Strictly Come Dancing version for families with tiny tots who were scared of Doctor Who's inter-galactic, mechanical nemesis!

Friday 15 December 2023

THE DAY WALT DISNEY DIED

When my friend, French Disney scholar Christian Renaut, visited me last month, he gave me a very special gift: a copy of the famous 24 December 1966 issue of the French magazine Paris Match featuring a grieving Mickey Mouse to mark the death of Walt Disney, nine days earlier.

The iconic cover painting was by French comic book artist, Pierre Nicolas, and the magazine contained a lengthy appreciation of the American filmmaker under the title, 'Adieu a Walt Disney - Il a Bati Un Empire Sur Une Souris'. Although very aware of this image – one that spoke to the global shock with which people received the news of Uncle Walt's death – I had never owned a copy.

It was a gift that brought back some powerful memories and, today, I am recalling an event that happened fifty-seven years ago today...

I am twelve years old and I'm getting ready for school and, suddenly, there is my father calling up the stairs: 'Brian... Walt Disney has died!'

Downstairs I can hear the murmuring drone of radio voices as my father –

busy brewing early-morning tea – listens, as he does every morning, to

the BBC Radio news programme, Today.

Maybe I should have have dashed downstairs to catch the reports, absorb

the details, gather up the tributes. After all, Walt Disney was my

hero. A strange idol for a young lad, maybe – but that is what he

was.

I collected every book, magazine and trivial snippet that I could find

about Disney and his studio. I was forever copying pictures of Disney

characters in my sketch-books – in fact my youthful ambition was to be a

Disney artist, to animate those fabulous beings that appeared in his

films. I longed to be a part of that mystical process that created

characters out of pencil, ink and paint and then imbue them with a power

to move people to laughter or tears. I was, I admit, obsessed by the

man and his movies.

Later that morning, on my way to school, I would buy the daily

newspapers and – in a corner of the playground at morning break – pore

over the obituaries; but, at the moment of first hearing the news, I had

only one response: I sat on the edge of my bed and, like Paris Match's Mickey Mouse, I cried.

For

the first time in my young life I experienced that bizarre phenomenon: a

feeling of overwhelming grief at the death of someone whom I did not

really know. Not only had I never met Walt Disney, I had – rather

surprisingly – never even written him a fan-letter. Yet, I felt, as

many others have felt on hearing of the death of some public figure,

president or pop-star – that I had lost a friend, been bereaved of

someone who held a unique place in my affections. The loss felt

achingly huge; a void had yawned open in my life that I doubted could

ever be filled...

For

the first time in my young life I experienced that bizarre phenomenon: a

feeling of overwhelming grief at the death of someone whom I did not

really know. Not only had I never met Walt Disney, I had – rather

surprisingly – never even written him a fan-letter. Yet, I felt, as

many others have felt on hearing of the death of some public figure,

president or pop-star – that I had lost a friend, been bereaved of

someone who held a unique place in my affections. The loss felt

achingly huge; a void had yawned open in my life that I doubted could

ever be filled...

In the four-and-a-half decades since that day, I have continued to study

– and occasionally write about – Disney's life and work. I have also

had the privilege of meeting many of those who knew, worked with, loved

and (sometimes) loathed the man. Such encounters have brought me very

close to feeling that I understand at least something of the unique

personality and character that was Walter Elias Disney.

But I have never been – never shall be – as close to him as I was on

that morning when my father called upstairs to tell me the news that

Walt Disney had died...

That memory triggers another from six or seven years later...

My early fascination with Disney movies had been suddenly intensified when I borrowed R D Feild's book, The Art of Walt Disney

from my local library. Here was someone who, unlike my Mum, didn't

think of 'cartoons' as kid's stuff you ought to have grown out of by the

time your voice breaks.

I wanted a copy of The Art of Walt Disney more

than anything else in the world and began scouring the second-hand

bookshops, which is how I stumbled on Fred Zentner. He later became The

Cinema Bookshop in London’s Great Russell Street, but when I first met

him he was selling film books, stills, posters and other gems –

including a copy of the much-lusted-after Art of Walt Disney

– from the basement of the Atlantis Bookshop, in Museum Street, just

round the corner from the British Museum. Once found, I began, bit by

bit, buying up Fred's stock of Disneyana.

Then came the day when he placed into my hands a copy of The Story of Walt Disney

by Walt's daughter, Diane Disney Miller, as told to Pete Martin. It was

a first edition American hardback, published by Henry Holt & Co

(New York) in 1956. It still had its original dustwrapper with a

portrait of Walt by studio artist, Al Dempster...

There, on the half-title page, in green biro, with that distinctive bold handwriting was the inscription...

It was his very signature – including the little circle over the 'i' in 'Disney' that I emulated in my own signature. This man – whom I had never met but who exercised an obsessive fascination over me – had held this book, opened it and inscribed his name inside.

'How much is it?' I whisper, holding my breath.

'Forty pounds,' he replies.

All those years ago, yet I remember the conversation as if it were yesterday.

It was an awful lot of money!

I wanted it! No, I craved it! But, FORTY POUNDS...

So, month on month, I made my pilgrimage to the Atlantis Bookshop, looked at the swirling green signature and paid another ten pounds.

Fast-forward thirteen years. I am standing in the Archive at the Walt Disney Studio in Burbank, California, talking with Archivist, Dave Smith. I am there researching a television documentary about EPCOT Center and I mention, in conversation, that the prize of my Disney collection was an autographed copy of The Story of Walt Disney

Dave Smith laughs and asks a question that almost brings the universe crashing down around my ears.

'Are you sure it's actually signed by Walt Disney?'

'Of course! It says so, in green biro: ‘Best Wishes Walt Disney’!'

'That may be,' he replies, 'but many people at the Studio, some of them distinguished animators, signed books and pictures on Walt's behalf.'

I look stunned. But, Dave goes on: 'The Disney signatures by these other artists are more like the famous logo signature that appears on Disney movies and merchandise. Walt's personal signature, however, is quite distinctive. Would you like to see a GENUINE Disney signature?'

Nothing could be simpler: within seconds I could know whether or not I owned the real thing. Or, I could leave things as they were. Except, of course, that now I couldn't. Dave Smith had sowed a terrible seed of doubt...

I hesitate for no more than a second: 'Yes, let's see a GENUINE Disney autograph…'

When, a few years later, I got to know Diane Disney Miller, I asked her about the book and she told me that her father used to sign copies for sale in the bookshop at Disneyland, which was very probably where my copy had originally been purchased.

A decade passed and I found myself in San Francisco working with Diane in co-presenting a radio series for the BBC about her father. On this occasion, I had carried the treasured volume with me and I asked her to add her signature to the book’s title page.

Appreciating the joke, she unhesitatingly agreed. Beneath the printed sub-title – ‘An intimate biography by his daughter, Diane Disney , as told to Pete Martin’ – she wrote: 'Actually, Brian – we know better, don’t we? Warmest, warmest regards, Diane.'

Nowadays, the autograph business is big business: copies of the recent reprint of The Story of Walt Disney with Diane's signature sell for several hundred dollars and someone, in a recent American auction, paid over three thousand dollars for a copy of the original edition signed (also in green biro!) by Walt.

This blog post is based on an earlier posting from December 2012, since when David R. Smith and Diane and Ron Disney have passed away.

For the story of the making of the Paris Match cover-painting see this interview with artist Pierre Nicholas by my colleague, Didier Ghez on his blog, Disney History.

Wednesday 13 December 2023

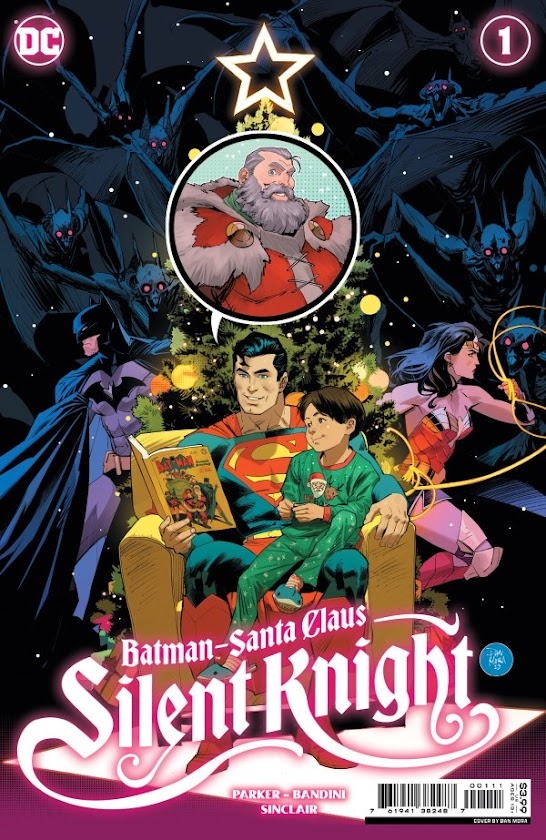

THE ART OF THE COMIC-BOOK (CHRISTMAS SPECIAL!)

Dan Mora's art (Cover A) for Batman/Santa Claus: Silent Knight #1. Published, DC Comics, December 2023.

I'm still waiting for my copy, but here's what we know about the comic:

SANTA CLAUS IS COMING TO TOWN!

The four-part crossover event of a generation begins when a not-so-jolly St. Nick hits Gotham City to investigate a brutal crime in the days leading up to Christmas… What manner of man or beast could have committed such atrocities?!

With the help of his former student, Batman, Santa will team up with the heroes of the DC Universe to right this wrong or the world wakes up to coal in their stockings!

A brutal, two-fisted holiday tale of hope, wonder, and monster

hunting is the perfect treat to ring in the holidays it’s Claus in

canon!

And here's a scattering of preview pages, written by Jeff Parker with art by Michele Bandini.

And to add a little Christmas nostalgia, here's a seasonal Batman comic cover from days of yore, beginning with Batman # 27 from (curiously) Feb-March 1945...

Tuesday 12 December 2023

GINGERBREAD HOUSE DAY

December 12th:

HAPPY GINGERBREAD HOUSE DAY!

Illustration:

Kay Nielsen (18886-1957) from Hansel and Gretel and Other Stories by

the Brothers Grimm (1925)

The tradition of making decorated edible houses from gingerbread began in Germany in the early 1800s, allegedly popularised following the publication, in 1812, the dark fairy-tale of Hansel and Gretel as told by the Brothers Grimm. In the tale, the abandoned children, lost in a wood, discover original the house "built of bread, and roofed with cakes, and the window was of transparent sugar.” In later tellings, the bread became gingerbread inspiring German bakers to craft small decorated edible houses from lebkuchen, the popular spiced honey biscuits.

"...It was now three mornings since Hansel and Gretel had left their father's house. They began to walk again, but they always came deeper into the forest, and if help did not come soon, they must die of hunger and weariness. When it was mid-day, they saw a beautiful snow-white bird sitting on a bough, which sang so delightfully that they stood still and listened to it. And when its song was over, it spread its wings and flew away before them, and they followed it until they reached a little house, on the roof of which it alighted; and when they approached the little house they saw that it was built of bread and covered with cakes, but that the windows were of clear sugar. 'We will set to work on that,' said Hansel, 'and have a good meal. I will eat a bit of the roof, and you Gretel, can eat some of the window, it will taste sweet.' Hansel reached up above, and broke off a little of the roof to try how it tasted, and Gretel leant against the window and nibbled at the panes. Then a soft voice cried from the parlour:

'Nibble, nibble, gnaw,

Who is nibbling at my little house?'

The children answered:

'The wind, the wind,

The heaven-born wind,'

and went on eating without disturbing themselves. Hansel, who liked the taste of the roof, tore down a great piece of it, and Gretel pushed out the whole of one round window-pane, sat down, and enjoyed herself with it. Suddenly the door opened, and a woman as old as the hills, who supported herself on crutches, came creeping out. Hansel and Gretel were so terribly frightened that they let fall what they had in their hands. The old woman, however, nodded her head, and said: 'Oh, you dear children, who has brought you here? do come in, and stay with me. No harm shall happen to you.' She took them both by the hand, and led them into her little house. Then good food was set before them, milk and pancakes, with sugar, apples, and nuts. Afterwards two pretty little beds were covered with clean white linen, and Hansel and Gretel lay down in them, and thought they were in heaven."

[Read more about the artist here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kay_Nielsen ]