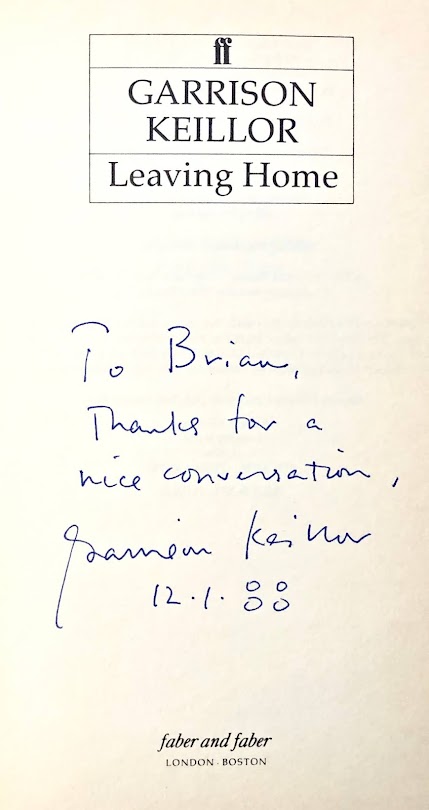

This is the first of an occasional series of posts in which I'll be sharing details of signed volumes in my book collection.

I start with P L Travers' Mary Poppins and the House Next Door, the last story about the magical nanny.

I

have a number of books inscribed and signed by Travers, but I've chosen

this particular title because it was her last, because she gave it to

me when it was first published in 1988 and because, at that time, we

were working together for the Walt Disney Studio on Mary Poppins Comes Back a planned (but unrealised) sequel to the Studio's celebrated 1964 Oscar-winning triumph.

This

also gives me the opportunity to re-post an essay I wrote fifteen years

ago about my very first encounter with the woman who gave us the

Practically Perfect Mary Poppins...

TEA WITH MARY POPPINS

I was going to tea with Mary

Poppins!

Well, no, not exactly, but I was going to tea with P L

Travers, who had written the Mary Poppins books; and, at that precise

moment, I was walking down a street of neat-and-tidy-looking houses that

reminded me very much of Cherry Tree Lane…

True, Shawfield Street – off the King's Road in London’s Chelsea – didn’t boast

any really grand houses (with two gates) like that owned by Miss Lark and none

of them were quite as unusual or as exciting as the ship-shape home of Admiral

Boom… But, as I arrived at the door of number 29, I felt as if I might expect

to find Robertson Ay asleep on the doorstep or hear the argumentative voices of

Mrs Brill and Ellen coming up from the basement.

This all happened over twenty years ago, but I remember it now as vividly as if

it were only yesterday…

I'd been invited to come to tea at four o'clock and I was a little early – ten

minutes early to be precise – because I really didn't want to be late and

keep Mary Poppins waiting...

I went up the steps to the front door – which, rather surprisingly, was painted

candyfloss pink – and I rang the bell.

Silence.

I rang again.

Still silence.

Had I got the wrong day, I wondered.

Then a window, two storeys up, flew open and a head popped out and asked, in a

brisk tone: "Are you Brian Sibley?"

I said that I was.

"Well," said the head, "you are early!" And the window

rattled shut again.

I waited. And I waited. For the full ten minutes I waited – until the clock on

a nearby church struck 'four'. Only then did a woman with curly grey hair and

bright forget-me-not-blue eyes open the door.

So, this was P (for Pamela) L (for Lyndon) Travers…

I noticed that she was wearing a

pair of 'sensible shoes' of the kind Mary Poppins wore; but, in contrast, she

sported a very un-Poppinsish dress with lots of frills and flounces, a

number of jingly-jangly bracelets and bangles (rather like those favoured by

Miss Lark, I thought) and a chunky turquoise necklace.

After my wait on the doorstep, I was a little nervous, but she welcomed me in

with a smile, threw my coat over the back of a noble rocking-horse who galloped

up the hallway and showed me into the room where, many times afterwards, I

would come to have tea and talk with the woman who introduced the world to Mary

Poppins.

When Jane and Michael Banks once asked Mary Poppins who she would choose to be

if she wasn't Mary Poppins, she replied, in her sharp, non-nonsense tone: "Mary

Poppins." It is a typical Poppins response: supremely confident, yet –

at the same time – as mysterious and elusive as the place where a rainbow ends…

And, sometimes, P L Travers could be much the same. For one thing, that was not

her real name: when she was born, in Australia in 1899, she was called

Helen Lyndon Goff.

Then, as a young woman she became

an actress and a dancer and took 'Pamela' for a stage name (because she thought

it sounded pretty and "actressy"), followed by 'Lyndon' (her own

second name and a reminder that her ancestors came from Ireland, the land of myths

and stories) and, finally, 'Travers' which was her father’s first name.

Travers Goff had

died when Pamela was seven-years-old and she never forgot how much she had loved

and missed him. Mr Banks in the stories is, in some respects perhaps, owes something to her father and,

although Pamela used to tell people that he was a sugar-planter in Australia, in

truth at the time that she was born Goff was working in a bank – just like Jane

and Michael’s father.

It was never easy to get factual detail from Pamela and she was

especially enigmatic is asked about the creative processes behind her

book. She would get especially irritated if you asked about how she came

to 'create' Mary

Poppins. firmly making it clear that she had 'discovered' rather than

'invented' the character – but, as with so many things in Pamela’s life,

you never quite knew…

She told me, for instance, that

Mary Poppins had first blown into her imagination – rather as she blows into

the lives of the Banks family – when she was recovering from an illness in an

old country cottage in Sussex. She said that somewhere – in that strange state

between being ill and getting better – the idea of a person like Mary Poppins

had come to her.

The truth is that,

several years earlier, she had written a short story entitled 'Mary Poppins and

the Match Man' that was published in a New Zealand newspaper and this story was, in fact, an

early version of the second chapter of Mary Poppins in which Bert

accompanies her on her 'Day Out' and they enjoy a wonderful tea with heaps of

raspberry jam-cakes!

What is certain is that, during that illness, she came up with ideas for new stories about the character and wrote them down. Mary Poppins, was

published in 1934, with illustrations by Mary Shepard, the daughter of the man

who had drawn Winnie-the-Pooh.

The following year, she wrote her second book, Mary

Poppins Comes Back, and, after a nine-year gap, the third book in the

series appeared. Pamela had wanted to call it Good-bye, Mary Poppins,

but eventually – after her publisher begged her not to be quite so final – it

was renamed Mary Poppins Opens the Door.

And, as it happens, it wasn't goodbye to Mary Poppins because, eight

years later, she wrote Mary Poppins in the Park following which the practically

perfect nanny reappeared in various spin-offs including an alphabet book Mary

Poppins from A to Z (which, for some reason, was subsequently translated into

Latin) and a book of stories and recipes entitled Mary Poppins in the

Kitchen. Late in life, the author wrote two more slim volumes: Mary

Poppins in Cherry Tree Lane and, finally in 1988, Mary Poppins and the

House Next Door.

"If you are looking for autobiographical facts," P L Travers once

wrote, "Mary Poppins is the story of my life." This seems an

unlikely claim when you think that Mary Poppins goes inside a chalk pavement

picture, slides up banisters, arranges tea-parties on the ceiling and

has a carpet bag which is both empty and yet contains everything.

But if we take her at her word, we can find many things in her books that

spring from her own life and shaped the stories she told…

For example, several of her fictional characters have names borrowed from

people Pamela had known in her childhood - among them a strange little old

woman with two tall daughters who ran the local general store where the young

Pamela bought sweets. Her name, of course, was – as it is in the stories

– Mrs Corry.

As for Miss Poppins herself, her first name was probably inspired by the

younger of Pamela’s two sisters who was known in the family as 'Moya' – the

Irish version of ‘Mary’.

As for 'Poppins'… Well, Pamela never gave any clues as to where that name came

from. But when she first arrived in London to work as a journalist, she used an

office near Fleet Street and on her way to visit nearby St Paul's Cathedral –

home to the Bird Woman – she would have passed a little lane with the curious

name, 'Poppins Court'.

Unlike

today's street signs, early London gazetteers did not include the apostrophe

and 'Poppins Court' was once the site of a 14th Century inn called 'The

Poppinjay' that was owned by the Abbots of Cirencester and had an inn-sign

displaying the Abbey's crest: a parrot-like bird.

And while we're talking parrots...

Although she

and her sisters never had a Mary Poppins for a nanny, they did have an Irish

maid named Bertha –– or maybe she was called Bella, Pamela pretended she could

never quite remember! Bella (or Bertha) was a marvellous character with almost

as many eccentric relatives as Mary Poppins.

What’s more, Bertha – or Bella – possessed something that was her pride and

joy: a parrot-headed umbrella. "Whenever she was going out," Pamela

once told me, "the umbrella would be carefully taken out of tissue-paper

and off she would go, looking terribly stylish. But, as soon as she came back,

the umbrella would be wrapped up in tissue-paper once more."

You will remember that Mary Poppins always carried her umbrella, regardless of

the weather, simply because it was too beautiful not to be carried.

"How could you leave your umbrella behind," asks the author, "if

it had a parrot’s head for a handle?"

"Spit-spot into bed," was a favourite phrase of her mother's,

and other bits of Mary Poppins' character were clearly inspired by Pamela's

spinster aunt, Christina Saraset, whom everybody called 'Aunt Sass'. She was a

crisp, no-nonsense woman with a sharp tongue and a heart of gold who, like Mary

Poppins, was given to making "a curious convulsion in her nose that was

something between a snort and a sniff."

When Pamela once suggested to her aunt that she might write about her, the

elderly lady replied: "What! You put me in a book! I trust you will

never so far forget yourself as to do anything so vulgarly disgusting!"

This indignant response was, apparently, followed up with a contemptuous, "Sniff,

sniff!"

Now,

doesn't that sound just like Mary Poppins? Certainly I can report that P

L Travers herself said something along the same lines

to me, when I rashly suggested, one day, that I might write her life-story!

As a young girl, Pamela took dancing lessons and there seems to be dancing, of

some kind or other, in every one of the books: remember Mary Poppins joining

all the birds and beasts at the zoo in dancing the Grand Chain? Or the Red Cow

who catches a falling star on her horn and can't stop dancing?

And,

speaking of stars, reminds me that, as a child, Pamela had been captivated by the

beauty of the constellations she saw in the clear southern skies above her home

in the Australian outback. She never lost her fascination with star-gazing and there are stars scattered

throughout the pages of all her books. In one story, Maia (one of the stars in the constellation Pleiades),

comes down to earth to do her Christmas shopping; in another, Mrs Corry, her two

gargantuan daughters and Mary Poppins paste Gingerbread Stars on to the night

sky.

Over the years I knew Pamela, we had many conversations but the one I

remember most clearly took place not long before she died at the grand age of

96 and it was also about a star.

I had asked her if she thought perhaps another story – maybe one last tale

about Mary Poppins – might come to her. "I think it might," she

replied slowly, "because, the other day, on the street outside, I found a

star on the pavement!"

"A star?" I repeated, with surprise.

"Yes," she said softly, "a star. Go and look for it yourself. I

hope I shall find out where it came from and what it is doing there."

It was dusk when I let myself out of the candy-pink door of 29 Shawfield Street

that particular afternoon and headed off to look for that star. Light was

failing, but I found it, at last: just as Pamela had said – a star-shape,

faintly but clearly marked in the surface of a paving stone.

A puzzled

passer-by looked quizzically at the man staring intently at what looked like a

very ordinary piece of pavement.

Doubtless

it was some rouge imprint on the surface from the manufacturing of the

cement paving-stone, but I was remembering the words of the old

snake, the Hamadryad, on that night of the full moon when Mary Poppins

took

Jane and Michael to the zoo:

"We are all made of the same stuff... The tree

overhead, the stone beneath us, the bird, the beast, the star - we are all one,

all moving to the same end..."

Like Mary

Poppins, P L Travers saw – and gave others the ability to see – the

magical in very ordinary and everyday things.

She had discovered something as rare and amazing as a star in a London street

and, then, she had given it away...

I hope she found out why it was there…

Of course, Mary Poppins would have the answer, but, as you know, she

would never, never tell...

© Brian Sibley, 2006, 2021

Illustration: Mary Poppins and the Hamadryad by Culpeo-Fox; all other illustrations by Mary Shepard